Nationalisms in Ceylon – By Dr Harold Gunatillake

Highlights

In Singapore & Australia, the Sri Lankans are proud to call themselves Singaporeans and Aussies, respectively.

The same: Sri Lankans land in Katunayake, come home for a holiday, and mind-orient themselves to call themselves “Sinhala Buddhists”, a term referring to the majority ethnic group in Sri Lanka who follow the Buddhist faith. This is my observation.

- Sri Lankan Australian who came with me on the same plane and spat on the pavement after alighting in

- I just retorted that you wouldn’t do that in

- Prompt, the answer came,” This is my ”

- I suppose that would be the patriotic feeling!

Is it feasible to create separate nations for each nationality on our island?

The concept of nationhood and its implications for Sri Lanka’s diverse ethnic tapestry, which is currently marked by tensions and conflicts, are the subject of intense debate. In an intriguing forum post, Dilrook Kannangara posits that the path to harmony lies in establishing three distinct nations within the island, each catering to a significant ethnic group. This proposition suggests that by relocating a mere 15% of the population, the remaining 85% would continue

their lives unaltered, potentially resolving the longstanding geopolitical tensions with local and international ramifications.

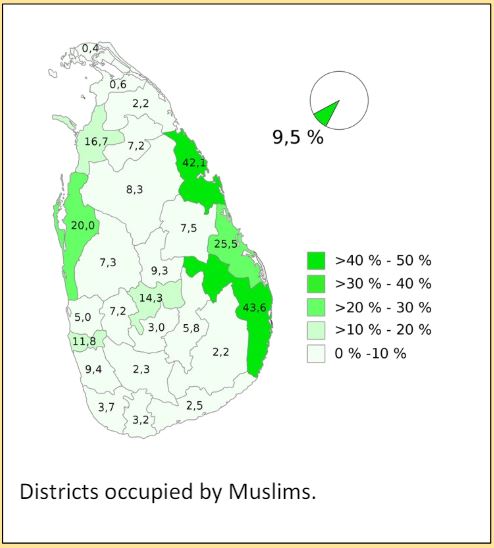

Kannangara’s vision entails the creation of Tamil Eelam, Muslim Eelam, and a Sinhala-centric nation, a tripartite division aimed at granting full nationalistic benefits to each group. Yet, the practicality of such a division raises complex questions, particularly concerning the Muslim community, which is dispersed across the island, thriving in enclaves from Matale to Kadugannawa. In Akurana, for instance, a bustling township stretches over five miles, with commerce flourishing well into the night, starkly contrasting the early evening stillness of Kandy’s streets.

This raises the question of whether a similar division has succeeded or failed in other countries with diverse ethnic populations.

The Eastern Province, too, is predominantly Muslim, as evidenced by the 2012 census. Beruwala and the southern reaches down to Hambantota are also Muslim strongholds. The challenge becomes one of logistics: how can these widespread communities be consolidated into a singular nation feasibly?

Similarly, while historically rooted in the Jaffna Peninsula, the Tamil population has a significant presence in Colombo, particularly in the prestigious Colombo 7 district. Relocating such well-established individuals poses its own set of dilemmas.

While Kannangara’s proposal addresses the intricate puzzle of national identity and coexistence, it also opens Pandora’s box of socio-economic and cultural considerations that warrant a deeper exploration beyond the surface-level allure of a tri-nation solution. The discourse on nationalism in Sri Lanka is indeed multifaceted, requiring a nuanced approach that carefully weighs the aspirations of all communities against the practicalities of geographical and demographic realities.

Written by Dr Harold Gunatillake-now residing in Kandy, Sri Lanka